5 Things You Need To Know About Past Muslims in Singapore Bicentennial

5 Things You Need To Know About Past Muslims in Singapore Bicentennial

Singapore is a multicultural nation that prides itself on its religious and racial harmony. Since attaining independence in 1965, Singaporeans have been living in harmony, through respecting ethnic, religious and cultural differences of various communities. Today, Singapore is the most diverse nation in the world, where Muslims, Christians, Buddhists, Taoists, Hindus and other religious groups coexist peacefully.

Muslims in Singapore continue to thrive and adapt to the changing landscape of the modern and globalising Singaporean society. We have been integrating with people of other religious and ethnic communities, and consider this, and no other places, as our home as our homeland. However, this positive religious outlook that we embrace today is the legacy that we inherited from the early generations of Muslims that chose to reside and be the citizens of this nation-state. While, over time, there have been external forces that seek to instill doubt and promote exclusivist and segregationist manifestations of our faith, we remain steadfast and resilient in holding on to our values as Singaporean Muslims. This is the sacred legacy that our pioneer generations of Muslims had embraced, as they continue to call Singapore home in post-separation Singapore. Despite being the numerical minorities, our pioneers chose to stay and, together with other communities, build this nation for future generations.

As Singapore commemorates our bicentennial in 2019, let us look back on how and why Muslims in the past chose Singapore as their home and raised their families in this multicultural island city-state.

1. WHY MUSLIMS CHOSE SINGAPORE AS THEIR HOME

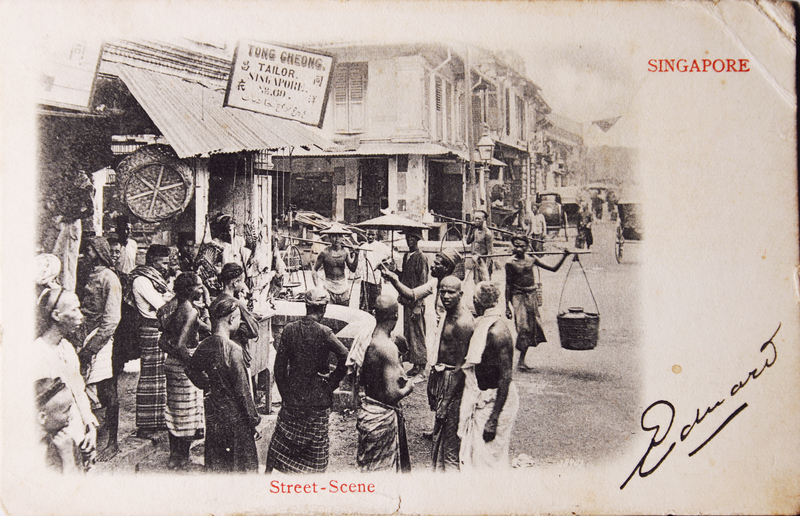

In the 19th century Singapore, Islam continued to grow rapidly with the arrival of immigrants, especially from South Asians and the Middle East. This is in addition to the existing residents, and the migration of the Malays from the nearby islands of Bugis, Riau and Java in Indonesia.[1] Demographically, Muslims in Singapore consisted of the Malays from the Archipelago, which formed the majority, together with a significant number of Arab immigrants and the Jawi Peranakan (local-born Muslims who were the offspring of mixed-parents of South Asians and Malays).[2]

The strategic geographical location of Singapore made this island an important port and regional trading centre, which attracted Arab traders and Indian merchants. This eventually led to the growth of the Muslim community in Singapore.

2. ROLE OF SINGAPORE IN THE HAJJ JOURNEY

Singapore played a pivotal role in the development of Islam in the region. It was the centre of transit for many hajj pilgrims. Many of these pilgrims, that came from various parts of the Malay Archipelago, temporarily settled down in Singapore before embarking on their journey to the holy city of Makkah. Some of them came to Singapore, prior to their pilgrimage, to find jobs to fund their pilgrimage trip to the Holy Land[3]. Some made enough money and left for Makkah and returned to their homeland after their pilgrimage. Others returned to Singapore and resided temporarily after completing their pilgrimage to work to earn enough money before returning to their homeland. Singapore played a pivotal role as an important hallmark in the region that facilitated the journey of the pilgrims to Makkah. Not only had Singapore functioned as a convenient stopover for the pilgrims by providing various hajj-related services, but it also provided platforms for pilgrims to find financial means to perform their pilgrimage[4]. The benefits of Singapore being a transit for hajj pilgrims also led to the expansion of the Muslim population on the island. There were significant numbers of pilgrims, who upon returning from Makkah, decided to reside in Singapore permanently, with many marrying the locals.[5] In addition, the economic opportunities in Singapore served as a pull factor that enticed some of the pilgrims to reside in Singapore. Among those who came to Singapore with the aspirations of performing the hajj in Makkah, there were also some who had postponed their plan due to financial difficulties and eventually stayed in Singapore to earn a living with some who never actually made it to Makkah, but resided in Singapore permanently.[6]

3. SINGAPORE AS THE EPICENTRE FOR PROGRESSIVE ISLAMIC THOUGHT IN THE REGION

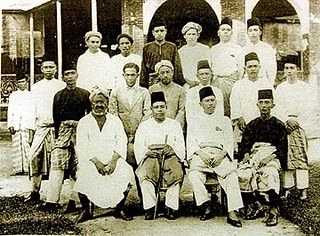

Besides being the regional centre for hajj transit, Singapore also became the crucible for reformist ideas and a regional hub of modern Islamic education. Singapore became the launchpad for the spread of Islamic reformist thought in the Archipelago. Prominent Muslim scholars like Syed Sheikh Ahmad al-Hadi and Sheikh Muhammad Tahir Jalaluddin were able to spread their reformist ideas on Islamic thought more freely in Singapore. Under the influence of reformist scholars like Muhammad Abduh and Rashid Reda, Syeikh Ahmad al-Hadi and Sheikh Muhammad Tahir Jalaluddin were known as the ‘Kaum Muda’.[7]

The ‘Kaum Muda’ called for the intellectual revolution of the Muslims minds in the region. As the region began to face the wave of modernization, the spread of reformist ideas within the Muslim circles began to gain significant momentum, especially in Singapore. Facing the prospect of having to face modernity in the Middle East, Muhammad Abduh from the Al-Azhar University in Egypt encouraged the Muslims to retrieve their rich intellectual heritage and to return to the practices of ijtihad in understanding the Quran and the Hadith.[8] They believed that Islam is compatible with modernity and in harmony with rationalism and modern science.

This was necessary to ensure that Islam remains a dynamic religion and blind imitation can be avoided. The ‘Kaum Muda’ encouraged Muslims in Singapore to accept ideas of modernity and ideas from the "West" as long as they do not conflict with the main principles of Islamic teachings[9]. This reformist idea gained momentum in the 19th century Singapore as the Muslim community had to respond to the forces of modernization and its encounter with the Western influences during the British administration of Singapore. As Singapore became a melting pot of cultural traditions and major crossroads of diverse religious groups, the Muslims henceforth embraced an inclusive religious outlook that fit their cosmopolitan context and was in harmony with their religious tradition.

One of the initiatives started by the ‘Kaum Muda’ was to reform and modernize Islamic education in Singapore. The new religious education model introduced by the ‘Kaum Muda’ led to a paradigm shift of Islamic learning in Singapore. They introduced a holistic model of education which incorporates both the religious and modern sciences in the curriculum.[10] This has provided the Muslim community with an alternative source of religious education other than the traditional religious schools. This new model of religious education was therefore a transformative initiative undertaken by the ‘Kaum Muda’. It equipped students with comprehensive knowledge and relevant skill sets that allowed Muslims to widen their employment opportunities during the British administration of Singapore.[11]

4) SINGAPORE AS THE REGIONAL HUB OF ISLAMIC LEARNING

One of the religious schools established by the ‘Kaum Muda’ was Madrasah Al-Iqbal. Established in 1908, this madrasah offered various subjects which included the Quranic learning, Arabic language, Moral education (akhlak), Islamic Jurisprudence (fiqh), Geography, History and Mathematics. The madrasah applied the pedagogical approach of critical thinking and discussions instead of rote learning which was applied in many of the traditional Islamic schools.[12]

The lifetime of Madrasah Al-Iqbal, however, was not long as it was forced to shut down as a result of financial constraints. Nonetheless, the madrasah education continued to flourish after the closure of Madrasah Al-Iqbal, when many of the Arab merchants in Singapore decided to build madrasahs as part of religious endowments (waqf). This led to the establishment of Madrasah Aljunied which attracted many students from around the region. This subsequently led to the founding of several other madrasahs, and a total of six continue to shape religious education in Singapore today.

5) SINGAPORE AS A CENTRE FOR ISLAMIC LITERARY TRADITION

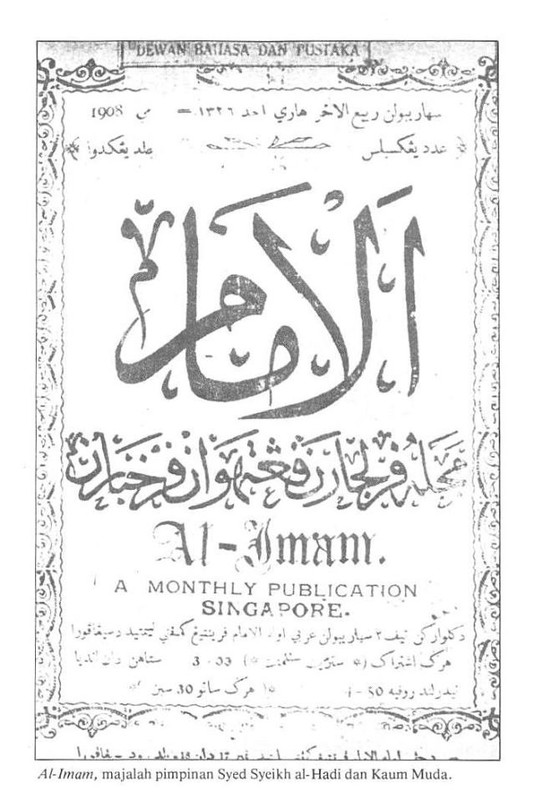

In addition to the educational transformation which seeks to incorporate Islamic religious instruction with modern sciences, Singapore also functioned as a centre for Islamic publications. One of the journals published in Singapore was Al-Imam journal, published in 1906 by the ‘Kaum Muda’.

This journal which was published in the Malay language was the replica of Al-Manar journal published in Egypt.

The main content of Al-Imam centred on the idea of reform, where the writers usually called for Muslims in the region to develop an adaptive outlook to modernity through synthesizing it with the Islamic values and practices without having to neglect their religious ethos and identities[13].

Clearly, the history of Islam in Singapore has been intellectually rich. The experience of modernity during the period of the British administration of Singapore demonstrated a dynamic Muslim community in the island-state. Facing challenges of modernity, Islam continues to flourish in Singapore. The historical experience of Islam in Singapore clearly shows that past Singaporean Muslims had been fairly adaptive and transformational in their religious tradition. This is, in essence, an inherent value of the Islamic tradition which promotes progressiveness, inclusivity and humanity.

The strategic geographical location of Singapore, located at the crossroads of major international trade, added to the vibrancy of Islamic thoughts by Muslim reformists made Singapore “the thriving cosmopolitan centre by the early 20th century”[14]. The Muslim community in Singapore has long adopted a cosmopolitan and inclusive religious outlook as they faced the challenges of modernity in the early history of Singapore.

The history of Islam has demonstrated that, indeed, Muslims in the past have been able to live peacefully and fit in the multicultural and modern Singaporean society. As we are faced with emerging issues of our times, our rich tradition of Islam and the values that we hold on to should be sufficient in guiding us as to how we can navigate our identity as both Muslims and as Singaporeans. Indeed, we are confident with our faith tradition and as Muslims, we will continue to play our part as pro-active citizens in this beloved nation of ours.

References:

[1] William, R. Roff (2009). Studies on Islam and Society in Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Press. pp.75-pp.76

[2] Ibid.

[3] Hadijah Rahmat (2005), Kilat Senja Sejarah Sosial Dan Budaya Kampung-Kampung Di Singapura, Singapore: HSYang Publishing Pte. Ltd., p.15

[4] William, R. Roff (2009). Studies on Islam and Society in Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Press. p.80

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid. p. 82

[7] William R. Roff (1967). The Origins of Malay Nationalism, Singapore: University of Malaya Press.

p. 66.

[8] Ibid

[9] William R. Roff (1962). Kaum Muda-Kaum Tua: Innovation and Reaction Amongst the Malays 1900-1941, in Papers on Malayan History, ed., K.G. Treggoning, Singapore: Journal of Southeast Asian History, 1962, pp. 169-170.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Kamaludeen Mohamed Nasir dan Syed Muhammad Khairudin Aljunied (2009). Muslims as Minorities: History and Social Realities of Muslims in Singapore, Bangi: Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, p. 44.

[12] Chee Min Fui (2006). The Historical Evolution of Madrasah Education, in Noor Aishah Abdul Rahman and Lai Ah Eng, ed., Secularism and Spirituality: Seeking Integrated Knowledge and Success in Madrasah Education in Singapore, Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International, pp.6-22.

Armando Salvatore and Martin van Bruinessen (2009) ed. Islam and Modernity: Key Issues and Debates. Edinburg: Edinburg University Press. pp. 253

[14] Hussin, Mutalib (2010), Religious Diversity and Pluralism in Southeast Asian Islam: The Experience of Malaysia and Singapore, in K.S Nathan (ed.) Religious Pluralism in Democratic Societies, Singapore: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, 36-60, p. 45