Islamic Calligraphy Facts That Will Blow Your Mind

Art unites. Such is the nature of this world. For centuries, civilisations have witnessed the unifying force of the creative world, with the power to gather collective minds through the admiration and appreciation of beauty. This force is much more so prevalent in our time, the digital age. With only a tap on our digital devices, our eyes can be treated to a masterpiece belonging to someone from other parts of the world. Thus, we are ‘unified’ and connected through a ‘share’ or a ‘follow’ on their social media accounts.

In Singapore, this ‘unifying force’ of arts can be seen in the various art programmes and activities organised by many associations. Their attempt to leverage the arts as one of the factors to bring our multi-racial and multi-religious community together has proven to be a successful affair.

PAssion Arts Festival 2019 returns with "Gardens of HeARTS". Photo credit: People's Association website

One such event would be the yearly PAssion Arts Festival organised by the People’s Association. Their return this year will showcase more than 200 art installations co-created by 30,000 residents, commemorating Singapore’s Bicentennial while celebrating National Day. The art installations throughout Singapore is a product by people of all walks of life coming together to experience and appreciate beauty.

ARTS IN THE ISLAMIC TRADITION

Arts in our Islamic tradition covers a wide range of creative practices with each of them grounded in the same discipline of craftsmanship, guided by skill and wisdom, all in search of perfection in the representation of The Divine. Its defining role in unifying the Muslim civilisation of different geographical localities can be seen in various forms. From the melodic hymns of poetry to the geometrical designs of architectural marvels can all be adapted to contain a common civilisational identity.

Islamic designs at the Alhambra palace in Granada, Andalusia, Spain

Islamic designs at the Alhambra palace in Granada, Andalusia, Spain

One of the most esteemed of these creative practices is the art of writing. Writers of the past assumed important roles such as the official scribers of the Caliphs, the copyists of the Quran and the designers of the inscriptions seen on the buildings of the Islamic world. They were all motivated by the Quranic verse:

ن ۚ وَالْقَلَمِ وَمَا يَسْطُرُونَ

Nun, by the pen and what they inscribe (68:1)

The Prophetic Sunnah also emphasises on the importance of learning and writing thus giving the pen an elevated status in the tradition. This branch of Islamic art is also highly valued due to its significant role in preserving the Quran by giving it the form that we see today. In this article, we will explore 3 interesting things about Islamic Calligraphy that you may not know.

1. DEVELOPMENT OF ISLAMIC CALLIGRAPHY

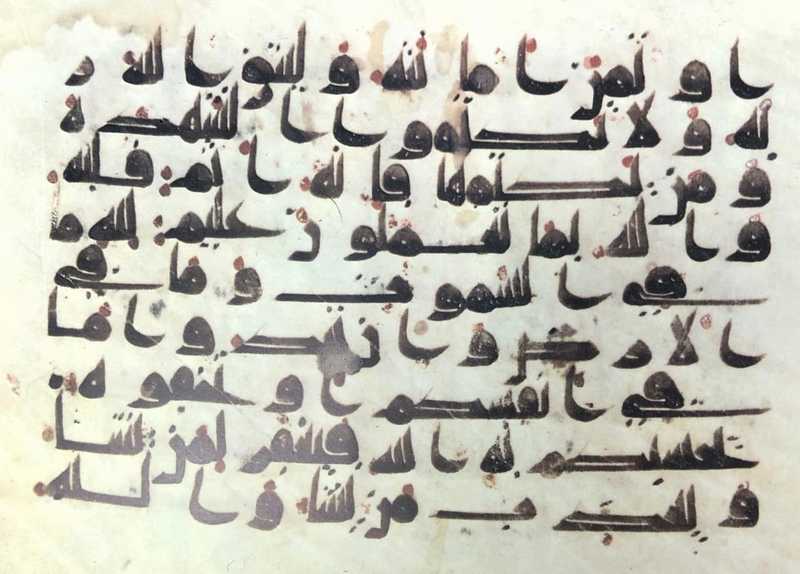

The earliest recorded writing of the Quran written in the Hijazi script can be traced back to the early eras of the Islamic Civilisation. The Hijazi script, a writing characterised by a slight slant to the right was subsequently replaced by the Kufic script. The term Kufic is a general term to describe scripts which were more angular in nature, and it contains many sub-scripts.

A page from a mushaf in Kufi script. Written in the 9th century AD with Resam Uthmani according to Abu Al-Aswad Ad-Du'ali's diacritical system. Photo source: The Art of Calligraphy in The Islamic Heritage, IRCICA

For the sake of simplicity, the two main subgroups of this script which were commonly used to write the Quran are the Kufic and the Eastern Kufic scripts. During the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, curvilinear scripts which were more cursive in nature were developed by scribers and copyists of the Quran for efficiency while writing, the most common one of these curvilinear scripts was known as Naskh.

The Naskh script then evolved greatly through a period of five hundred years until it reached a spectacular degree of refinement during the Ottoman period. This great achievement happened under the hands of great master calligraphers such as Syeikh Hamdullah and Hafiz Osman. The Qurans written in the Naskh script towards the end of the Ottoman empire by the likes of the calligrapher Muhammad Shauqi Effendi and his contemporaries are still being used as references by calligraphers of our time to write the Quran. One such example of a Quran written in recent times is the Quran produced by King Fahd complex in Madina written by the calligrapher Uthman Taha.

Madinah mushaf written by calligrapher Uthman Taha. Photo credit: The Cognate

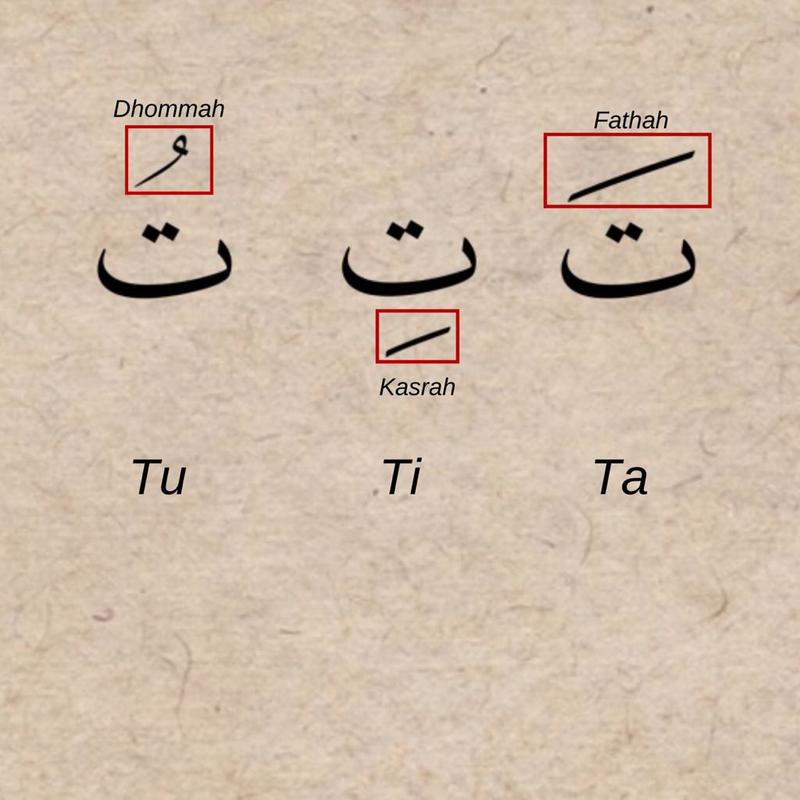

The system of diacritics in Quranic writing was first introduced by Abu Aswad Ad-Du’ali in the 7th Century. Diacritics are markings placed on different letters and short vowels to indicate a particular pronunciation. In the initial years, circular dots were used to represent the Fathah, Kasrah and Dhommah. A dot above the letter represented the Fathah, a dot below the letter represented Kasrah and a dot in front of a letter represented Dhommah. The placements mimicked the shape of the lips when pronouncing the respective short vowels.

From then on, scholars of the Quran worked hard to improve the diacritical system in accordance to the needs of Muslims from each era. Some methods which were used were colour codings, empty dots and shaded dots. Another prominent figure is the linguist Khalil bin Ahmad Alfarahidi who is credited for creating the diacritical system that is still in use in the modern Quran read by Muslims today.

2. CULTURAL ATTRIBUTES IN ISLAMIC CALLIGRAPHY

With the acceptance of Islam in different regions and cultures, the Arabic language and script increased in prominence. People started to hold the Arabic script in high regard as it is the gateway to understanding the religion and the Quran. They also needed a way to express the new terms that they learnt such as 'solat', 'zakat', 'halal' and 'haram'.

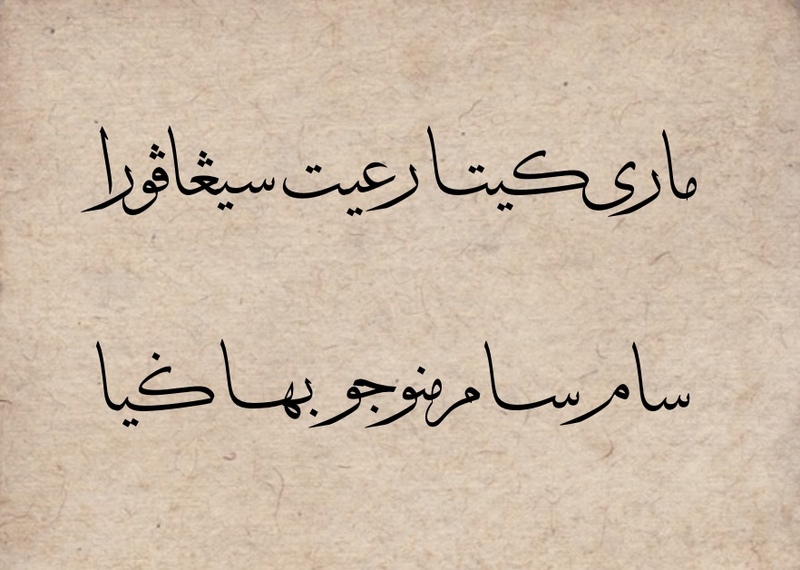

Jawi Writing - Verse one of Majulah Singapura written in Jawi with the Thuluth script and wooden pen by Ustazah A’tii Qah Suhaimi

Jawi Writing - Verse one of Majulah Singapura written in Jawi with the Thuluth script and wooden pen by Ustazah A’tii Qah Suhaimi

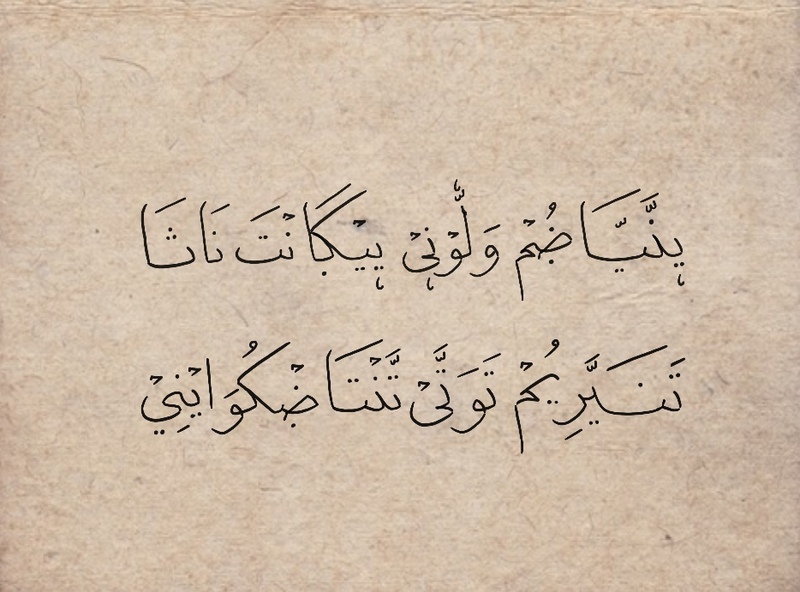

As a result, various cultures started to express their respective languages in the Arabic script, with each sound from the source language being represented by a corresponding letter from the Arabic alphabet. Extra letters were also added to integrate sounds which were not available in the Arabic language. Some examples are Jawi, that was used to write the Malay language and Arwi, which was used to write the Tamil language by the Muslims of Tamil Nadu.

Arwi Writing- Supplication Ratib Jalaliyah written in Arwi with the normal pen in Arabic Penmanship by Ustazah A’tii Qah Suhaimi. Photo source: TAQWA

Arwi Writing- Supplication Ratib Jalaliyah written in Arwi with the normal pen in Arabic Penmanship by Ustazah A’tii Qah Suhaimi. Photo source: TAQWA

At a glimpse of an untrained eye, it will look as if all these languages, when written, come from one universal language used by Muslims all over the world. It is recorded that no less than 50 languages had adopted the structure of Arabic script for writing. Nowadays, some of them are rarely practised, and most of them are already lost in history.

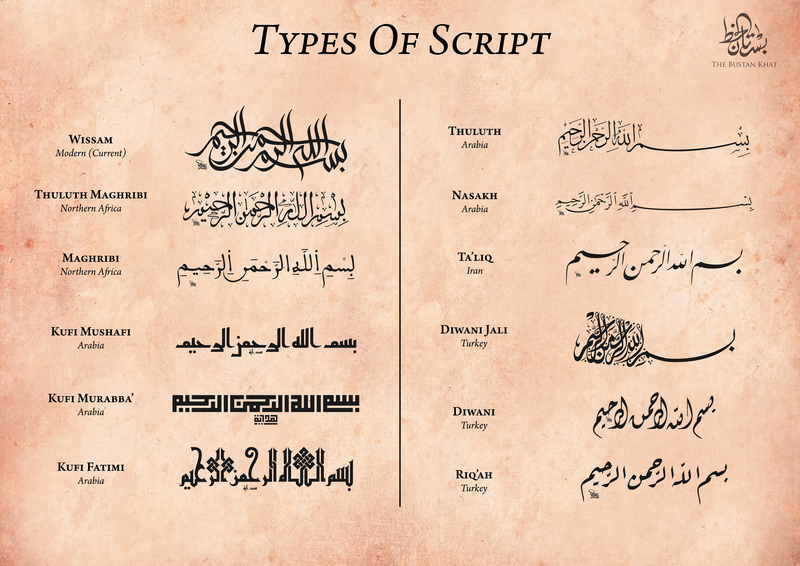

Another brilliant example of the influence of different cultures to the art of Islamic writing is the existence of various types of scripts created by calligraphers originating from different geographical areas. These unique scripts, such as the Maghribi script from Morocco, the Farisi or Ta’liq script from Persia, the Naskh and the Thuluth script from Arabia and the Diwani and the Diwani Jali scripts from Turkey are all written in completely different forms. Despite that, they share a standard system which ensures the presence of geometric harmony and uniformity in all of them. Their representation of the diverse cultures from around the world also contains in itself the unity that echoes through the rules of the standard unit of measurement used in Islamic Calligraphy.

Types of script written by Singaporean calligraphers of The Bustan Khat.

Types of script written by Singaporean calligraphers of The Bustan Khat.

3. ELEGANCE AND PRECISION OF ISLAMIC CALLIGRAPHY

The geometric system adhered by calligraphers is widely attributed to the treatise of the Proportioned Script (Al-Khatt Al-Mansub), developed by Ibn Muqla and his brother in the 10th century AD and was further refined by Ibn Bawwab in the 11th century AD. There are two main points from this treatise that is regarded by calligraphers as the navigating principles when creating a new script.

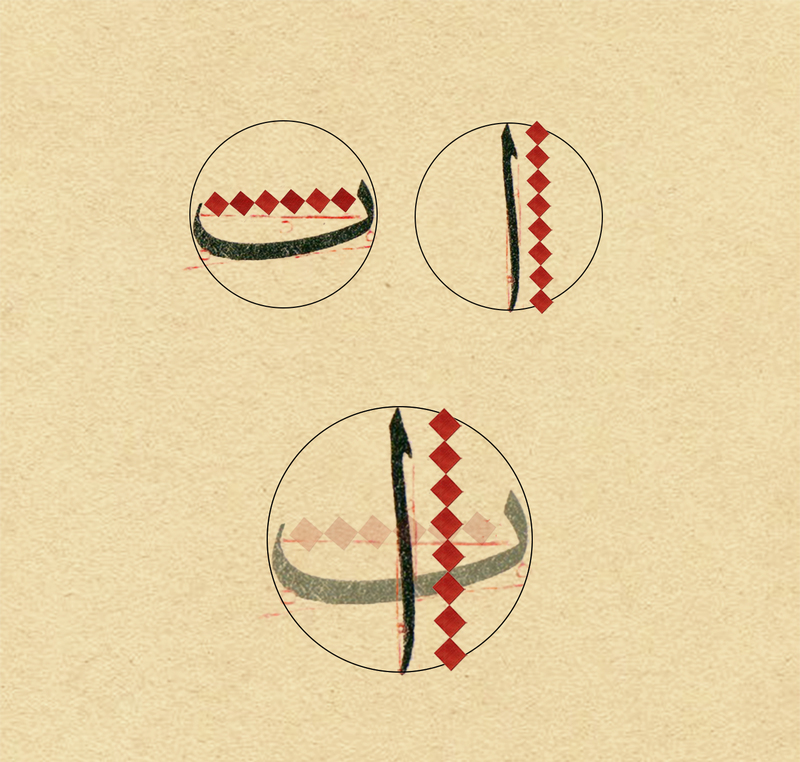

The first point is the Rhombic Dot (Nuqto) which is used as the metric unit to measure length. By ensuring that all letters and words can be broken down to a specific number of dots means that the script is equipped with an in-built measuring system to direct calligraphers when writing. Calligraphers who mastered the measurements of each letter will acquire the skill of repetitive uniformity while writing and more interestingly, they are able to write without a base line.

Illustration of the system of the Proportioned script for the letters Alif and Ba in the Thuluth Script written by Ustazah A’tii Qah Suhaimi

The second point is that the size of each letter in a particular script is created from the size of the circumference of the letter Alif. This ensures proportionality and the proper incorporation of the Golden Ratio to each stroke when writing.

The development of this system represents the desire to reflect divine perfection by generations of calligraphers. Despite having to conform and unite under a single system of measurement, calligraphers from different parts of the world still managed to formulate distinct styles. This development proves that having a single system to guide does not restrict. Instead, it may even push the creative potential of calligraphers to achieve the impossible.

Islamic art encapsulates the extraordinary phenomenon of unity in diversity. Within it is a type of cultural synthesis, so rich, as it contains the characteristics of each individual culture from diverse geographical areas. By the virtue of that, Muslims are also able to identify that the differences embody the characteristics of a unified source. Hence, they will always be able to relate to one another and feel a sense of belonging towards all of the various types of arts practised within the tradition.