Is Social Responsibility a Religious Duty?

Introduction

From the Australian bushfires to armed conflicts and not forgetting the ongoing pandemic that has crippled the global economy, 2020 has exposed and exacerbated fault lines in societies globally. But more importantly, it has underlined the significance of interconnectedness between humans and the natural world that requires one to see the world as a tapestry of cause and effect.

Every religion, including Islam, calls on its followers to responsibly position oneself within this dynamic tapestry to maintain the natural order that is part of God's cosmic plan. Failure to preserve this order results in imminent chaos and strife. Unfortunately, this connection has gradually diminished as we have created a hyper-consumerist, hyper-individualistic world.[1]

Islam, founded on individual and collective responsibility, introduced a social revolution in the context in which it was first revealed. The Prophetic message first gravitated towards the marginalised and oppressed in society due to its liberatory ideals that broke the chain of exploitation and oppression. It then calls on every individual in society to materialise these ideals to preserve social institutions and order. This article aims to briefly share a few personal reflections that represent the social imperative of Islam, which is anchored on values such as justice, mercy, and solidarity.

1) Tauhid as a Guide for Social Action

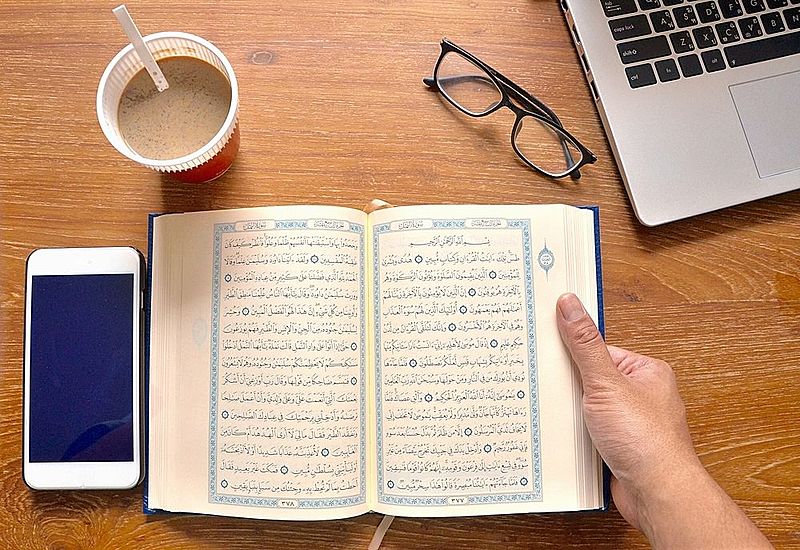

Tauhid comes from the root word w-h-d, which means to be alone and one. According to Ibn Manzur, Tauhid is "faith in God, with whom there is none other, the Solitary without a partner. The notion of Tauhid is the defining doctrine in Islam that binds the ethical system in the Quran. While deliberations concerning Tauhid have mainly focused on the nature of man's response to God, Muslim thinkers such as Ali Shariati, Fazlur Rahman, and Farid Esack have identified Tauhid as a system aimed at realizing the oneness of God in human relations and institutions.[3] Furthermore, the Quran has underlined our duty to establish and maintain God's moral and social order to preserve Tauhid.

يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا كُونُوا قَوَّامِينَ بِالْقِسْطِ شُهَدَاءَ لِلَّهِ وَلَوْ عَلَىٰ أَنفُسِكُمْ أَوِ الْوَالِدَيْنِ وَالْأَقْرَبِينَ ۚ إِن يَكُنْ غَنِيًّا أَوْ فَقِيرًا فَاللَّهُ أَوْلَىٰ بِهِمَا ۖ فَلَا تَتَّبِعُوا الْهَوَىٰ أَن تَعْدِلُوا ۚ وَإِن تَلْوُوا أَوْ تُعْرِضُوا فَإِنَّ اللَّهَ كَانَ بِمَا تَعْمَلُونَ خَبِيرًا

“O, believers! Stand firm for justice as witnesses for Allah even if it is against yourselves, your parents, or close relatives. Be they rich or poor, Allah is best to ensure their interests. So do not let your desires cause you to deviate (from justice). If you distort the testimony or refuse to give it, then ˹know that˺ Allah is certainly All-Aware of what you do.”

(Surah An-Nisa, 4:135)

Therefore, to love God is to fulfil our responsibilities in maintaining Tauhid's individual and social planes. A selective understanding of Tauhid would do God an injustice. Any effort that supports the well-being of His creations is critical for a Tauhidic society.

2) Materialising Human Dignity as a Collective Whole

The scriptural vision of human dignity can be divided into two levels. The first level alludes to a metaphysical-ontological ground of human dignity where it is innate and conferred upon Man.

وَلَقَدْ كَرَّمْنَا بَنِي آدَمَ وَحَمَلْنَاهُمْ فِي الْبَرِّ وَالْبَحْرِ وَرَزَقْنَاهُم مِّنَ الطَّيِّبَاتِ وَفَضَّلْنَاهُمْ عَلَىٰ كَثِيرٍ مِّمَّنْ خَلَقْنَا تَفْضِيلًا

“Indeed, We have honoured the children of Adam, carried them on land and sea, granted them good and lawful provisions, and privileged them far above many of Our creatures.”

(Surah Al-Isra, 17:70)

According to Kamali, the above verse is an axiomatic representation of dignity given to man due to his ontological reality as the progeny of Adam. Accordingly, the children of Adam including the pious and the sinner are all endowed with dignity, nobility and honour. That is to say; human dignity is a proven right of every human being regardless of their colour, race or religion.[6] It cannot be made exclusive to any particular group or class of people. This brings us to the second level of dignity, where it is conceptually linked with righteousness (Taqwa).[7] According to Sheikh Raissouni, Taqwa is the source of ethics in Islam. It requires the believer to be fully aware and attentive of the consequences of his actions, whether it concerns himself, God, or any of His creations.[8] Draz further underlines that the flow of the entire ethical system in the Quran can be summed up in the concept of Taqwa. It brings together the deepest respect for the ideal and the pursuit of the highest good possible without contravening nature's laws.[9] Therefore, Taqwa should not only focus on our consciousness of God, but it should also include a lived concern and compassion for His creations.

Against this backdrop, God has entrusted men and women to establish his/her own dignity by offering the same conditions for others to be dignified. In this regard, the violation of human dignity implies a violation of human's responsibility to create the conditions for the advancement of human flourishing and the common good. In short, human dignity is not just a concept that is confined to the individual, but it transcends to embrace others as well. According to the Russian philosopher Dostoyevsky (d.1881), equality is grounded in human dignity. According to him,

“We should see each other as brothers first, and then there will be a brotherhood. Only then will there be a fair sharing of goods among brothers“[11]

3) Quranic Morality and Ethical Action

La Morale du Coran (The Moral World of the Quran) is considered one of the most essential books on Quranic morality in the 20th century. The author, Muhammad Abdullah Draz (d.1958) was a respected Azhari scholar who had immensely contributed to contemporary Islamic thought and Quranic studies. While morality is often perceived as an internal undertaking, Draz, in his masterpiece, argues that the Quran lays out practical moral qualities that inspire believers to ethical actions.[12] Thus, Quranic morality demonstrates both an internal and external state of expression.[13] According to Draz; ethics is what justice demands, while morality is what the soul aspires.[14] Therefore, a believer must be fashioned by the quality of justice and ensure that it is translated through his/her interactions. Hence, adopting the Quranic moral qualities should go hand in hand with doing good and contributing to humanity's general well-being. A moral Muslim should play an active role in improving the welfare of the community, nation-building and human development at large.[15]

4) Prophetic Ethics of Reciprocity

George Hourani (d.1984) states that a religious view of ethics is "believed to have been learned from God through prophetic revelation and associated divine sources”.[16] Here, we can understand that the Quran sets the standard of universal values, and the Prophet s.a.w, in his day to day life and through his multiple roles in society, demonstrated that those standards could be met. In essence, the Prophetic message is ethical in nature. It is narrated by the Prophet s.a.w. that

"Verily, I have been sent to fulfil and complete the moral character"

(Al-Adab Al-Mufrad)

The ethics of reciprocity or better known as the golden rule is a maxim that binds religions together. It encourages people to treat others the way they want to be treated. This maxim has become a guiding principle in interfaith engagements and the development of human rights norms.[18] Moreover, scholars have also regarded the golden rule to be the cornerstone of the Prophetic message. It was narrated by the Prophet s.a.w:

“None of you truly has complete faith until he loves for his brother what he loves for himself”.

(Sahih Al-Bukhari)

It is the most well-known statement that reflects altruism (al-īthar) in the Prophetic tradition. In a fractured world, embracing this message will allow us to focus on building bridges with our communities and reform our surroundings. It is unrealistic to think that the golden rule will solve the problems facing humanity. Still, it serves as a starting point to galvanize an innate collective moral consciousness that sees each other as a single body.

When a limb aches, the rest of the body responds with empathy and strives to restore the body's well-being. The fact that Imam Al-Bukhari (d.870) placed the above Prophetic narration in his book of faith (Iman), shows that abandoning the golden rule is detrimental to the faith of a believer. Therefore, a Muslim must recognise that having a good theology should not be at the expense of harming others. To embrace reciprocity as a social ethic is fundamental in developing a prosperous society that recognizes its human and civic duties.[20]

5) Maslaha and Human Responsibilities

The Islamic principle of maslaha that is commonly translated as the common good has been discussed by many jurists and ethicists. It can be regarded as one of the key objectives of the Shariah. Imam al-Ghazali sees maslaha as the pursuit of something beneficial (manfa’a) or to avoid something harmful (madarra).[21] More specifically, maslaha refers to everything that realises the preservation of the five principal values (al-usul al-khamsa)[22] — faith, the self, intellect, family and wealth.

Mafsada (corruption), on the other hand, refers to everything that removes all or some of these five principal values.[23] Since the Shariah is regarded as divinely ordained, it can be perceived that maslaha is God, acting with a normative vision through revelation to promote the well-being of His creations both in this world and the next. In this sense, maslaha creates a dynamic nexus between divine ideals and the human struggles to establish justice and social order.[24]

From an ethical perspective, there are two things that we should take into consideration when dealing with this dynamic concept. First, maslaha should not be mistaken with the utilitarian theory of Bentham.[25] An Islamic ethical theory should not be pigeonholed into a single idea as it demonstrates rigidity, which contradicts the Quranic morality.

According to Draz, the two key conditions of moral obligation in the Quran are the possibility of action and gentle practice.[26]Therefore, I would argue that maslaha is driven by teleological reasoning and fluidly moves between deontological and consequential moral reasoning. For example, the requirement for a mukallaf (a responsible and able-bodied Muslim) to fulfil the prayers is categorically ordained in revelation.[27]

However, in times of crisis, such as the pandemic that we are facing today, the Friday prayers are suspended to protect human life. This decision is guided by the Islamic legal maxim, “(valid) emergencies permit the unlawful” - Al-Darurat tubih Al-Mahzurat.[28]

Second, although deliberations on maslaha primarily deal with human well-being, it is crucial to recognise that Allah has created all living organisms to be interdependent to maintain the balance in nature. Since humans are created to be God’s steward on earth, it should also be in their best interest to establish a sustainable ecosystem that preserves the equilibrium of the natural world, and not cause harm (mafsada). Therefore, being critical consumers and conserving endangered species should fall under the purview of maslaha as it ultimately concerns the pursuit of human well-being.

6) Reconnecting with Mortality

The late German sociologist Zygmunt Bauman (d.2017) characterised the liquid modern society as constantly pursuing a goal but lacking a clear final destination. In response to this uncertainty, Bauman argues that it compels individuals to consume and turn them into objects of consumption to escape the insecurity and fulfil fleeting satisfaction.[29] For many humans, this end goal represents death as the culmination of life. The choices that we make today will determine our tomorrow. Therefore, the idea of death would urge us to be good and do good.

Unfortunately, today, death has been distanced from our reality. It is easier for us to forget death and harder for us to be reminded of our mortality. We tend to isolate and conceal death in unfamiliar spaces such as hospitals and hospices.

The consequence of this alienation is theologically profound. In the absence of death, we imagine that our lives are perpetual and disregard the Giver of life.[30] In turn, our relationship with His creations will be a mechanised and industrialised reality. For example, our consumption habits have caused conflicts globally and are arguably one of the primary factors concerning the pandemic's spread.[31] The Prophet s.a.w. has reminded us that:

“A gift to a believer is death”

(Shu’ab al-Iman)

Death is a mirror, and it is through this mirror that we construct our own life. Death would only be seen as a gift, depending on how we offer meaning to our life. It would profoundly impact how we value the sanctity of life and materialise love with the people around us, our environment, and ultimately God.

The disconnection from death would result in the evisceration of our morality and ethics. Sontag (d.2004) provides us with a stark reminder of our mortality. Everyone is born with dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and the kingdom of sick. Although we would naturally choose to identify as 'citizens of well', sooner or later, we are bound to be citizens of the other kingdom.[33]This realisation would vindicate the sanctity of life and make the journey from well to sick a dignifying one.

Conclusion

According to Alatas (d.2007), the Prophetic vision of society is freed from poverty.[35] To materialise this ideal, we need to be a society that sees beauty in God's painting and humanises relations with His creations.

On the contrary, an individualised community will further exacerbate the fault lines in society that have existed and are created due to the COVID-19 pandemic. To quote the renowned Indian author Arundhati Roy, perhaps we should see the pandemic as a portal between two worlds. "We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks, and dead ideas, our dead rivers, and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it".[36]An interesting point to reflect, research has shown that when the order of the natural world is disrupted, we lose our altruistic traits, and it turns us to be violent and hierarchical.[37]

It is with great hope upon reading this article that it would ignite change within the reader to rethink the roots of fault lines in society. To be loved by God requires us to bring benefit to others.[39]

Allahu A’lam.

[1] Hari, J. (2018), Lost Connections, Uncovering the Real Causes of Depression and the Unexpected Solutions, (pp.100-105), London:Bloomsbury Publishing.

[2] Esack, F. (1997). Qur'an, Liberation & Pluralism, An Islamic Perspective of Interreligious Solidarity Against Oppression (p. 90). London: Oneworld Publications.

[3] Mctighe, L. (2009). HIV, Addiction, And Justice: Toward A Qur’anic Theology of Liberation. In F. Esack & S. Chiddy, Islam and AIDS Between Scorn, Pity, and Justice (p.215). Oxford: Oneworld Publications.

[4] Quran, 4:135

[5] Quran 17:70.

[6] Kamali, M. (2002). The Dignity of Man. Cambridge: Islamic Texts Society.

[7] Quran 49:13.

[8] Raissouni, A. (2016). Ethics in Medicine: A Principle-Based Approach In Light of the Higher Objectives of Sharia. In Ghaly. M, Islamic Perspective on The Principles of Biomedical Ethics (p.223). London:World Scientific Publishing.

[9] Draz, M. (2008). The Moral World of the Qurʼan (p. 291). London: I.B. Tauris.

[10] Quran 17:70

[11] Dostoyevsky, F. (2004). The Brothers Karamazov (p. 290). New York: Barnes & Noble Books.

[12] Five critical elements that form the bedrock of Quranic morality: obligation, responsibility, sanction, intention and effort. Each element plays a vital role in the conscience of believers. The Quran demands believers to understand their moral obligation and responsibility. It would enable them to recognize sanctions in this world and the next, how their intentions have to be in line with their actions, and the exact contribution of their effort to their actions (Abdelgafar, 2020).

[13] Abdelgafar, B. (2019). Morality in the Qur'an, The Greater Good of Humanity (p. 159). Swansea: Claritas Books.

[14] Abdelgafar, B. (2020). Interview with Dr. Basma Abdelgafar on Morality in the Quran [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eJGrsz7kDYY

[15] Abdelgafar, B. (2018). (p,160).

[16] Hourani, G. (2009). Reason and Tradition in Islamic Ethics (p. 69). Cambridge, GBR: Cambridge University Press..

[17] Bukhari, Hadith 273

[18] Parrott, J. (2020). The Prophet’s Golden Rule: Ethics of Reciprocity in Islam. Retrieved 25 August 2020, from https://muslimmatters.org/2020/03/25/the-prophets-golden-rule-ethics-of-reciprocity-in-islam/

[19] Bukhari, Hadith 13

[20] Rabinovitch, S. (2018). Reciprocity, not tolerance, is the basis of healthy societies. Retrieved 25 August 2020, from https://aeon.co/essays/reciprocity-not-tolerance-is-the-basis-of-healthy-societies?fbclid=IwAR2k3JF-0QSy9l61cn980W9kfpCmDfZ3pDsERRXqyjM82fpkAwE6Bl78hn0

[21] Ramadan, T. (2016). Al-Maslaha (The Common Good). Retrieved 25 August 2020, from https://tariqramadan.com/english/al-maslaha-the-common-good/

[22] A study of the entire system of Islamic law would acquaint us with the fact that it protects five universal categories of well-being (maslaha/ masâlih): (1) religion (al-dîn); (2) life (al-nafs); (3) capacity (al-‘aql); 0 (4) progeny (al-nasl); and (5) property (al-mâl). Within each of these five universal categories, individual rules were further classified into primary (darûrî), secondary (tahsînî) and tertiary (tazyînî) to achieve one of the law’s five universal ends (Fadel, 2008, p.51)

[23] Setia, A. (2016). Freeing Maqasid and Maslaha from Surreptitious Utilitarianism. Retrieved 25 August 2020, from https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-482056305/freeing-maqasid-and-maslaha-from-surreptitious-utilitarianism

[24] Ezieddin, E. (2019) Islamic Normative Ethics in the Public Sphere: Maṣlaḥa and the Search for an Overlapping Consensus. Australasian Journal of Legal Philosophy, 44, (p.131).

[25] Fadel, M. (2019). Is Islamic Purposivism (maqāṣid al-sharīʿa) a Thinly-Disguised Form of Utilitarianism?. Retrieved 25 August 2020, from https://islamiclaw.blog/2019/09/05/is-islamic-purposivism-maqa%E1%B9%A3id-al-shari%CA%BFa-a-thinly-disguised-form-of-utilitarianism/

[26] Draz, M. (2008). The Moral World of the Qurʼan (p. 40).

[27] Qur’an 4:103.

[28] Muis: Office of the Mufti. (2020). Retrieved 25 August 2020, from https://www.muis.gov.sg/officeofthemufti/Fatwa/Fatwa-Covid-19-English.

[29] Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

[30] Nguyen, M. (2018). Modern Muslim Theology (pp. 30-33). Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

[31] Ellis, S. (2020). Why New Diseases Keep Appearing in China. Retrieved 25 August 2020, from https://www.vox.com/videos/2020/3/6/21168006/coronavirus-covid19-china-pandemic

[32] Al-Tirmidhi, Hadith 1609

[33] Sontag, S. (2001) Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors. London:Picador.

[34] Alatas, S.H. (2020) Islam dan Sosialisme (p.16).Selangor:Gerakbudaya.

[35] Ibid., (p.63).

[36] Roy, A. (2020, April 03). Arundhati Roy: 'The pandemic is a portal': Free to read . Retrieved August 25, 2020, from https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca

[37] Taylor, S. (2020, August 20). Humans aren't inherently selfish – we're actually hardwired to work together. Retrieved August 25, 2020, from https://theconversation.com/humans-arent-inherently-selfish-were-actually-hardwired-to-work-together-144145?utm_medium=email

[38] Esack, F. (1999). On Being a Muslim(p.12). New York: Oneworld Publications.

[39] Al-Tabarani, al-Muʻjam al-Awsaṭ, Hadith 6192